We Asked Gamers About Their Hard Days at Play NYC. Here’s What We Learned.

Our ability to feel is what makes us human. It is fundamental to who we are, underlying how we connect and the realities we co-create.

It supports our sense of self, helping us unpack our thoughts and reactions, build awareness of what's happening around us, and deepen our knowledge of ourselves in relation to the world we live in.

Games make us feel. They delight us, challenge us, calm us, frustrate us, connect us, and excite us. They're also uniquely captivating, not just in what they portray aesthetically and demand mechanically, but because of the state of embrace they insist on those who play them. Encountering a never seen start screen or the unopened box of a new tabletop game, we are ready, willing, and receptive to knowledge. Play's ability to get us to put our guard down, be curious, and engage with new possibilities helps create the conditions for transformation and meaningful learning.

Earlier this month, the iThrive team showcased at Playcrafting's Play NYC—an event that magnified the power of play and brought hundreds of game industry professionals, indie game developers, and game designers together to exhibit their games to players and peers. There, we shared Cadence, a single-player, text-based strategy game we created with the One Love Foundation and Playmatics, LLC. Cadence invites players to explore three of their friends' stories and converse with them via real-time dialogue choices that affect their friendships and outcomes. Building on One Love's mission to empower young people with the life-saving prevention education, tools, and resources they need to see the signs of healthy and unhealthy relationships, Cadence supports young people in learning to love better, in being with partners who practice healthy love, and communicating with loved ones who are in unhealthy relationships. While New Yorkers of all ages played a demo of the game and shared feedback, teens, many of whom went on to become members of our Teen Hub, were particularly moved by the game's storyline, mechanics, and captivating 2D art.

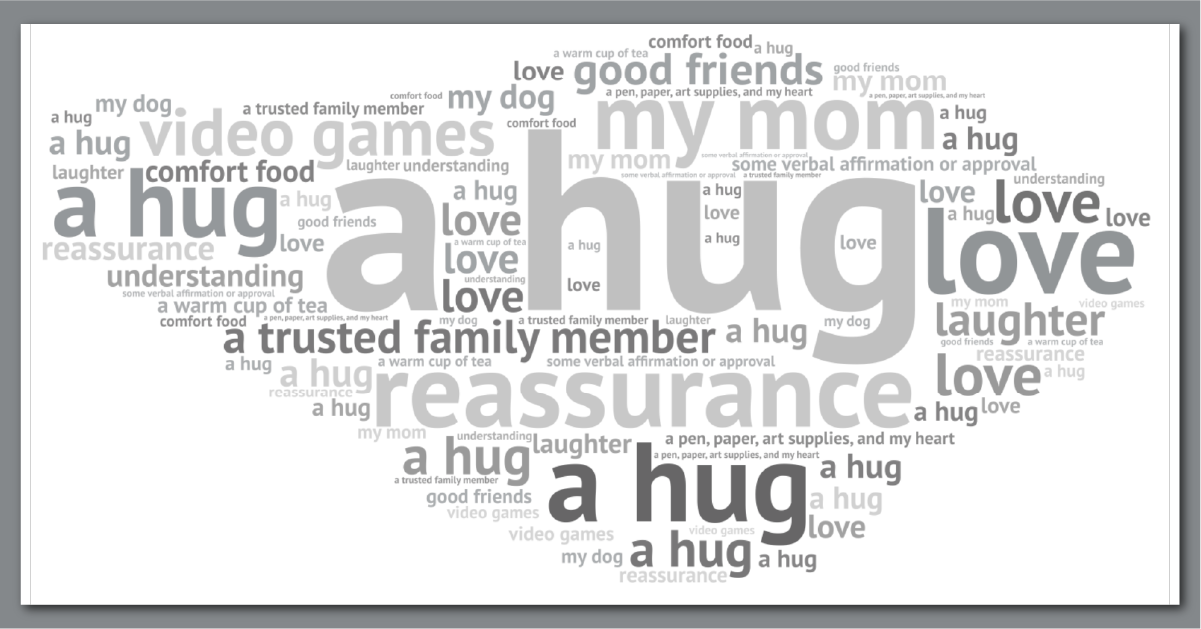

Beyond the valuable feedback we received on Cadence, slated for release later this year, the experience provided another opportunity for our team to create a forum for listening to and learning from young people. At PLAY NYC, we marked a large glass bowl with the question, "What makes you feel better on your hard days?", and teens and young adults anonymously shared the following:

ARE WE LISTENING?

Tucked in each of these answers is a guidepost for innovation—caring, joy, connection, self-expression. Creating safe spaces where teens are heard and listened to with the intent to understand them has guided our game development and experience design work over the last five years, and empathic listening and design is what has made the impactful play experiences we've designed with and for teens possible. The needs echoed and desires illuminated in the responses we elicit from young people in the safe spaces our social and emotional learning experts create (in this case, a glass bowl, and lime green Post-it notes) are folded into the game concepts we envision with clients and collaborators

Empathic listening has long been a driver of breakthrough thinking. Being in community with teens and young adults has helped us think expansively and collaboratively. We've found that empathy, when practiced consistently, is essential to transformative change and central to the knowledge-building and knowledge-sharing that informs the design of meaningful solutions.

iThrive's co-design approach, which gives teens the tools to step into their genius and explore their needs, is care in action. Our approach creatively empowers young people with new ways to tap into their genius, share their experiences and wisdom with others, advocate for the support they deserve, and create with us the experiences they want to see.

With the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reporting that nearly half of U.S.-based high school students are experiencing persistent feelings of sadness and hopelessness, it is on all of us in the game design ecosystem to create the spaces, in person and digital, to listen and effectively gauge the thriving of end users. With over 90 percent of teens and young adults self-identifying as gamers, every game designer, developer, and writer has the tools to meet them where they are and equip them with valuable knowledge, tools, and support. It is on all of us always to ask, "Are we listening?"

ARE WE SUPPORTING?

The learning that comes from listening allows all designers and developers to respond constructively, and offer support in meaningful ways. Games are already socially and emotionally valuable, and when tailored to teens and young adults' strengths, developmental needs, and insights, they become vessels for further social and emotional support.

Our adolescent development experts work with and for young people, and in partnership with libraries, museums, government agencies, and organizations that care about them, fully recruit the feelings that play evokes to support teens' social and emotional health. The science of adolescence and evidence-based practices that support positive teen growth are folded into the games, game-based tools, and interactive learning experiences we create. Questions like "How does this enliven teens to practice healthy skills like exploring their identity, engaging with their community, and taking purposeful action in the world?"; "How does this invite teens to regularly notice emotions, helping them notice the thoughts, sensations, and behaviors that accompany their feelings?"; or "How does this normalize help-seeking?" steer the game development process we lead, ending in a play experience that nourishes young people in ways supportive of their wellness, learning, and thriving.

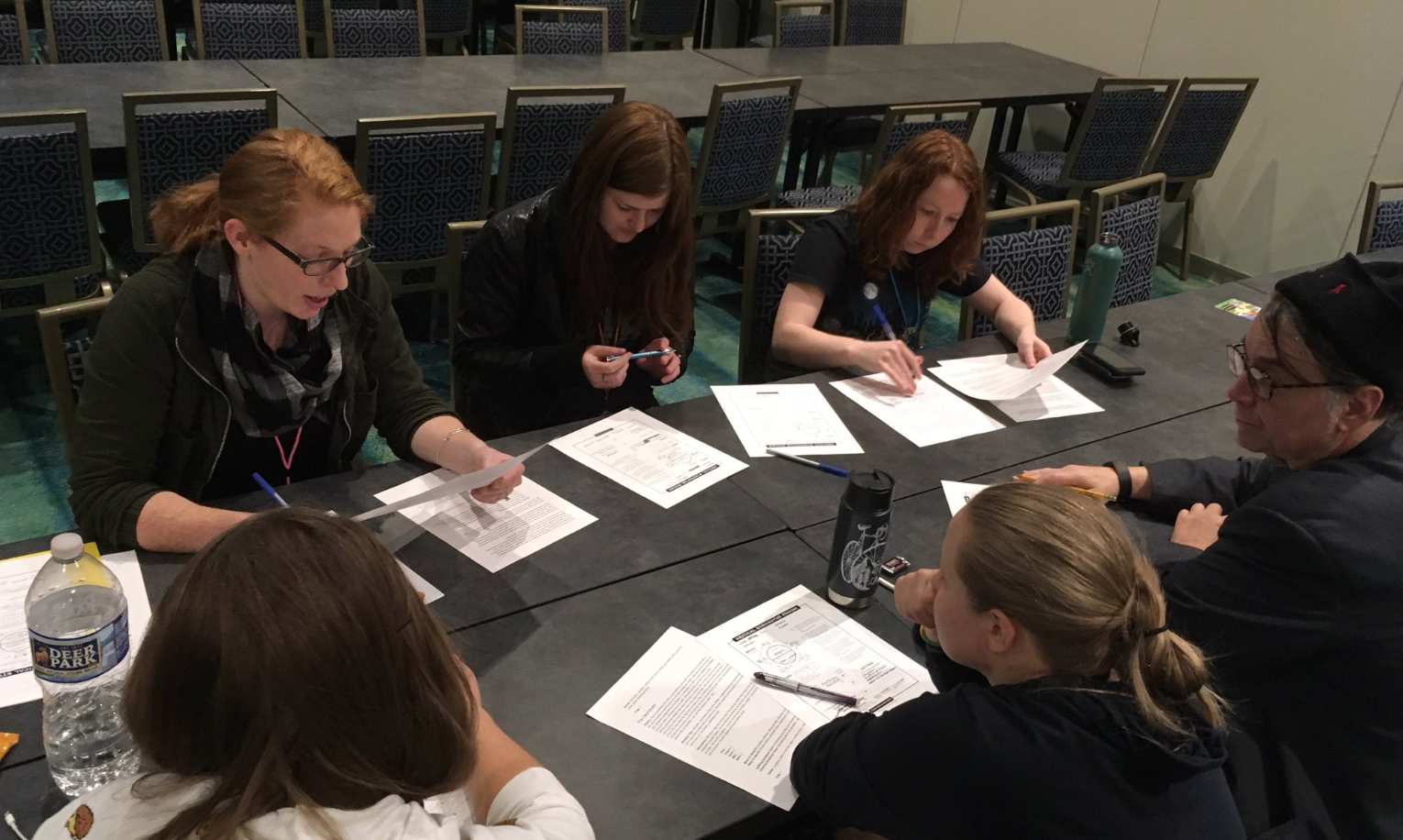

At Play NYC, we shared questions like these on a printout version of our 10 Things to Know When Designing for Teens resource, given to other game designers and developers eager to go beyond listening and to start responding and supporting young people's social and emotional needs. We're happy to now make that resource accessible to everyone and downloadable via the Resource Hub on our website.

Asking and listening helps us understand people and ideas. That insight and evidence-based practices nudge us toward wellness-supporting games and more impactful play experiences for young people. For the design team or studio looking to elevate the impact of the games they create for young audiences, connect with us today for a consulting report benchmarking your game in development against the science and sharing recommendations on ways to fold in social and emotional skill-building—a practice proven to protect and promote teen mental health.

Together, we can and should advance wellness wherever young people are. Join in.

The Teen Mental Health Crisis is Real. Game Designers & Developers Can Help.

This post is the last in our five-part series, Supporting Teen Mental Health, which shares tools and insights that support educators, parents, and youth-serving adults in showing up for teens in this moment of need. Read earlier posts in the series about mindfully managing difficult emotions, using social media actively and intentionally, nurturing the teen brain with school-based social and emotional learning opportunities, and applying culturally responsive approaches in therapeutic interactions with teens.

Veteran game designer, Jason VandenBerghe, wrote for iThrive Games in 2018 that "If we want to make a large, positive change in our world, I believe the best route is to focus on providing teens with better models for the world." If teens needed better models for the world four years ago, how much more do they—and all of us—need them in 2022?

This month alone, two 18-year-olds separately made the ruinous decision to commit mass murder—one in a racially charged event in Buffalo, NY, and the other in Uvalde, TX. U.S. teenagers wake up every day to more evidence of gun violence, societal strife, greed and corruption in places of power, shrinking opportunities for financial security, and the threat of climate catastrophe. It's no small wonder that rates of mental health struggles among teens are higher than ever.

Video games and social media are too often the easy scapegoats for teens' mental health challenges. In reality, the impact of digital technologies on youth mental health and well-being is complicated, and conclusions in the research are mixed. We know that's largely because "digital technologies" vary as widely as the teens who use them and the circumstances in which they're used. Of course, playing video games under some conditions can be disruptive to the healthy functioning of some, and can facilitate the healthy functioning of others. So, what's the responsibility of a game designer or developer?

At iThrive, we value and know that it is both possible and imperative to empathize deeply with and design ethically for teens. One of the best ways we've found to do this: Co-design with teens the digital tools they use. A youth-centered approach to digital technology design is among the recommendations put forth by the U.S. Surgeon General in his Advisory on Protecting Youth Mental Health. When we design with teens, for teens, the digital experiences they engage with are both likelier to do no harm at this vulnerable developmental moment, and likelier to amplify teens' immense capacity to thrive emotionally, socially, cognitively, and physically.

There's so much that's fascinating and motivating about the teen brain and how it's changing. For designers, we've boiled it down to a list of 10 things to know when designing for this unique window of both opportunity and vulnerability to best support teens' mental health.

TEENS ARE:

-

BUILDING HABITS FOR LIFE: Teens' brains are undergoing the last major restructuring of development, making the teen years the perfect time to build skills and habits that help them throughout life. But negative habits "stick" more at this time, too.

-

CATCHING ONTO YOU, FAST: Teens are getting wiser about the world. They're reaching a cognitive peak and learn very quickly. They easily see through attempts to manipulate or preach to them and don't respond well to hypocrisy or unfairness.

-

IN NEED OF POSITIVE CONNECTIONS: Above all, teens need access to strengthening experiences, environments, and relationships that help them grow in positive ways. They want to be close to adults, even as they figure out how to be more independent.

-

MORE TOLERANT THAN TEENS USED TO BE: Teens today value diversity and acceptance even more than previous generations. They care about authentic inclusion and diversity.

-

NOT JUST "WEIRD:" Obvious, but worth remembering, teens aren't just Western, Educated, and from Industrialized, Rich, Democratic countries. They need their uniqueness and diversity to be reflected in the spaces where they spend time.

-

SENSITIVE TO REWARDS, ESPECIALLY SOCIAL ONES: Teens have more dopamine circulating in their brains than adults. They are very sensitive to "feel-good" rewards like those in video games. Teens do riskier things when other teens are around, partly to earn status and respect.

-

STILL LEARNING TO CONTROL IMPULSES & EMOTIONS: Teens are still developing connections in the prefrontal cortex. They have a more challenging time controlling impulses and emotions and predicting the consequences of their actions than they will in the future.

-

IN NEED OF MORE SLEEP: Teens need more sleep than adults to thrive, and they might need support to make the best choices and set boundaries for their health.

-

FACING A LOT OF STRESS: Teens are under a ton of pressure. Also, if they are going to appear, most mental illnesses show up between early adolescence and young adulthood. Teens need ways to cope and to be able to seek help without stigma.

-

TRYING TO FIGURE OUT WHO THEY ARE: Teens want to try on different roles and expressions and figure out where they belong. They need social spaces to interact, experiment, negotiate, and resolve conflicts. But toxicity and bullying should be proactively prevented in these spaces.

So, if you're a designer or developer of experiences teens use, how much do you think about their needs at this developmental moment? What models of the world are you making for them? And are teens a part of your design process?

Creating spaces that foster teens' mental health and well-being is a team effort. iThrive is here to support you. We offer Game Design Kits, evidence-based guides to designing for mental health, and specific components of teen thriving like growth mindset and zest. We also specialize in custom design services that draw on teens' genius and creative problem-solving energy. Reach out to find out how you can use our co-design approach at your studio or organization.

One Thing Mental Health Practitioners Who Work With Teens Must Know

This post is the next in our series, Supporting Teen Mental Health, which shares tools and insights that support educators, parents, and youth-serving adults in showing up for teens in this moment of need. Read earlier posts in the series about mindfully managing difficult emotions, using social media actively and intentionally, and nurturing the teen brain with school-based social and emotional learning opportunities.

Teens' mental health difficulties and needs have peaked since the start of the pandemic, culminating in what leading U.S. child and adolescent health organizations have deemed a national emergency. As mental health practitioners strive to meet diverse teens where they are at this time of crisis—in part one spurred on and exacerbated by racial inequities—they need tools and approaches that offer authentic entry points for building rapport and trust.

The U.S. Surgeon General's 2021 Advisory, Protecting Youth Mental Health, stresses the need to "recognize that a variety of cultural and other factors shape whether children and families are able or willing to seek mental health services. Accordingly, services should be culturally appropriate, offered in multiple languages (including ASL), and delivered by a diverse mental health workforce." Using culturally appropriate tools and approaches invites teens and their families to engage as equal partners in improving and maintaining young people's mental health. Critically, this approach also amplifies and celebrates existing strengths and connections that are unique to each young person's cultural background and social network.

At iThrive, we've witnessed how games can be a powerful part of culturally responsive approaches to supporting teens' social and emotional skills, which are critical for mental health across the lifespan, both in schools and in therapeutic settings. That's because games of all kinds have the power to tell compelling stories, not just about the characters within them but about the players who play them, revealing truths about who they are and the world they inhabit. As one high school senior said of iThrive Curriculum: Museum of Me, our unit based around the game What Remains of Edith Finch: "You learn some things about yourself and others. It's nice to know that your [sic] not alone in seeing yourself a certain way. It's kind of relieving to know other people feel the same ways about themselves."

In an effort to help youth-serving practitioners better support teens with culturally responsive tools and approaches, iThrive's Senior Director of Learning Michelle Bertoli interviewed Lora Henderson, a licensed clinical psychologist, former educator, and assistant professor at James Madison University who specializes in supporting the mental health of young people in underserved populations. In the interview transcribed below, she shares best practices and tools — including game-based approaches — for engaging authentically with diverse teens in support of their health and healing. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Michelle: In your own work, how do you identify and define culturally responsive tools and practices?

Lora: I work at the intersection of education, mental health, and social and emotional learning. I define culturally responsive practices, or CRPs, as actions practitioners can take to build on students' strengths and cultural frames of reference. In the classroom, this might mean drawing connections between the curriculum and students' home lives and cultural experiences. In a clinical setting, it might include showcasing materials, games, books, and posters that reflect students' cultural backgrounds and experiences.

Michelle: And how do you get a sense of what's going to be culturally relevant and useful to students? It takes time to get to know them and you don't want to make assumptions.

Lora: Yes, that can be difficult because you don't want to fall into stereotypes about groups. We often go into our interactions with children and families with our own biases and assumptions about their cultural groups. Sometimes those things map onto their experiences and other times they don't. So, I do a lot of building relationships with kids, asking them what they did over the weekend, how their family celebrates holidays. Those small things aren't therapy, per se, but are really important to getting to know kids and their families and what culture means to them and looks like in their own contexts.

Michelle: At iThrive, we design our games and game-based tools with equity, representation, and accessibility as core pillars. From a practitioner's perspective, how do these design principles make a difference for supporting teen mental health and well-being?

Lora: We can expect youth to have improved outcomes when they can connect to the materials, games, or information being shared with them. When we design with youth, put them at the center, and make them experts, like everyone at iThrive really does, it can maximize positive youth engagement with the tools you're creating. At iThrive, it's a bidirectional process: the youth designers get to build social and emotional skills and increase their well-being, and peers who play the games also get to learn from the youth designers' expertise and experiences. That process can have large positive effects for the designers and their peers alike.

Michelle: What tools, including games or game-based approaches, do you use to strengthen young people's awareness and embracing of their cultural identities?

Lora: From my time as an elementary school teacher to my current role as an assistant professor and licensed clinical psychologist, my first job is to build rapport and authentic relationships with youth. All of the other positive outcomes are couched in that initial positive relationship that creates a safe space for youth and families to feel accepted. That's how I demonstrate my respect, openness, and acceptance of their cultural identities. In my classroom and therapy office, I ensured that the books, pictures, and posters reflected the diversity of my clients so that youth could see themselves in my office and know that it was a safe space to be themselves.

In therapy, I play lots of tabletop, board, and card games with youth. As one example, I've played a lot of Spades with Black families who play it at home, to bring an aspect of their culture into the room. I have emotions/feelings playing cards, so as we're playing Spades, and they get a "9" with an angry face on it, we talk about times when they were angry or observed someone else being angry, and how they managed those feelings. I really like to incorporate games that youth are already playing and then infuse mental health and social and emotional components into them. In in-patient settings, youth have taught me card games that they learned while in the hospital or juvenile detention. I let them lead the play. It's one way I demonstrate that I accept and value their lived experiences.

Michelle: How has embracing your own cultural identity as a practitioner helped you hone your professional skills? How have games played a role in this?

Lora: As a Black woman, I have had to examine my own biases and experiences to help me acknowledge the systemic racism that I experience in this country AND the privileges that I have as an employed, cisgender professional with a doctoral degree. While games have to be facilitated thoughtfully and in a sensitive way, gameful activities like "Step in the Circle," "Cross the Line," "Four Corners," and the "Privilege Walk" have helped me with my own personal exploration. I have moved away from the "Privilege Walk" activity because it visually moves privileged individuals ahead and those with less privilege behind and can perpetuate bias, but it was a meaningful activity for me when I did it about 10 years ago. It was the first time that I was really able to reflect on my privileges and challenges as a Black woman. The other activities that I mentioned still have the visual component of stepping into the circle, crossing the line, or going to the corner that aligns with youth experiences, but they remove the cumulative visual effect of moving further ahead or further behind.

Michelle: How would you recommend other clinicians who are not as practiced in culturally responsive approaches with young people begin to build those muscles?

Lora: The best way to become more culturally responsive is to engage with youth and listen to them. Reading the literature and learning about cultural responsiveness, humility, and competence is important, and still there's nothing like just talking to youth. Inevitably, they'll tell you that it doesn't work exactly how it's explained in textbooks or scholarly articles.

But before talking to youth, anyone who wants to be culturally responsive needs to engage in self-reflection about their own biases and assumptions about people from other cultural groups. It can help to have a group that you talk to about these things for accountability and outside perspectives. I can't stress how important doing that personal work is before stepping into work with youth. We don't want them to be our test subjects or to cause unintentional harm by doing things we think are culturally responsive but might be missing the mark and actually doing harm.

Talk to youth about what they like to do, what they enjoy, how they celebrate holidays. Get to know them in an authentic way.

Michelle: How can practitioners manage the fear or uncertainty they may have about making mistakes or unintentionally doing harm when striving to be more culturally responsive?

Lora: I think mindfulness-based techniques are really helpful. If you feel yourself getting nervous or unsure, stop and take a few breaths. Center yourself and remind yourself why you're doing this work. So many of us go from meeting to meeting to facilitating a workshop, etc. Sometimes just taking that breath can help settle your nerves and get you ready for those intersections.

Also, I think it can be fine and even acceptable to acknowledge differences between youth. You can highlight both obvious differences and similarities to help youth notice commonalities they share. Let youth know that you're trying, that you're maybe from a different cultural background and you might stumble, and you want to know about it if you do so you can do better next time. You need a safe space, too, in order to learn when you've made a mistake. It all comes back to authentic relationships because if you don't have that and you miss the mark, youth won't tell you. They might keep trucking along with the program or activity but the outcomes may not be as positive as they could have been.

Michelle: What are some resources you would recommend to practitioners who want to learn more about culturally responsive practices?

Lora: I lean heavily on the Double-Check framework. It's from education but applies in therapy as well. A shorthand tool it uses is the acronym CARES: Connections with curriculum, Authentic relationships, Reflective thinking, Effective communication, and Sensitivity to students' cultures.

For people who want to go even deeper, I also recommend this review of CRPs from an education perspective.

Michelle: Thank you so much for your time and insights, Lora!

[End of Interview]

Mental health practitioners seeking to find new ways to meaningfully engage and support teens from a diversity of backgrounds can also find inspiration in iThrive's Game Guides, which highlight unique ways to check in with teens and touch on their emotional experiences through the lens of some of their favorite games including Minecraft, Fortnite, and Super Smash Bros. Ultimate.

iThrive's Game Design Studio Toolkit is another rich resource for using games as systems to engage teens in complex, aspirational thinking that has its roots in awareness of their unique personal experiences. Individuals who aspire to something even more innovative can also make use of iThrive's design services to envision and realize completely fresh game-based approaches.

What are some ways you use games or game-based approaches in therapeutic interactions with young people? Let us know at contact@ithrivegames.org!

How Social and Emotional Learning Nurtures the Teen Brain

This post is the next in our series, Supporting Teen Mental Health, which shares tools and insights that support educators, parents, and youth-serving adults in showing up for teens in this moment of need. Read earlier posts in the series about mindfully managing difficult emotions and using social media actively and intentionally.

"My understanding of myself changed a great deal."

"I learned how to be a better friend."

"I was able to deal with aspects of myself that I never really had before."

"It's nice to know that you're not alone in seeing yourself a certain way."

Each of these quotes shared by teens is a testament to what happens when schools provide them with meaningful opportunities to actively explore who they are and who they want to be in the world and to build the social and emotional skills that support their mental health and development.

Adolescence is the last major window of neuroplasticity, a time when the teen brain is open to incredible learning potential, on one hand, and heightened vulnerability, on the other. Half of all serious mental health disorders in adults begin by age 14, making early prevention and intervention critical. High quality social and emotional learning interventions have been linked to reduced symptoms of anxiety and depression and lower levels of emotional distress among young people. But even teens who are not experiencing mental health struggles have specific developmental needs when it comes to maintaining and improving mental health. These include having opportunities to figure out who they are, to experience autonomy and independence, and to refine their relationship skills as interactions with both peers and adults in their lives become deeper and more complex. Each of these skills, and many more, are the aim and outcome of quality school-based social and emotional learning efforts.

The U.S. Surgeon General's Advisory on Protecting Youth Mental Health notes the role school communities can play in helping young people find "a sense of purpose, fulfillment, and belonging," supporting them in "managing their mental health challenges." Accordingly, they recommend that educators, school staff, and school districts continue to "expand social and emotional learning programs and other evidence-based approaches that promote healthy development." Mental health supports fall on a continuum of care, and high quality social and emotional learning programs are a "Tier 1" intervention, meaning they provide fundamental coping skills all students in a school community need, even as some students will require more intensive and targeted types of mental health support.

The Advisory mentions that creating the foundation for "a healthier, more resilient, and more fulfilled nation" where young people can thrive begins with creating "accessible space in our homes, schools, workplaces, and communities." To us, "access" means meeting teens where they are developmentally with tools they are familiar with and inviting them to the table when those tools are being developed to share how and what they want to learn. At iThrive, we specialize in creating social and emotional learning experiences that enlist the power of play and respond to teens' unique developmental needs. By design, we prioritize teen voice, personal relevance, and student choice in what we create with and for young people. The genius, creativity, and insight of the teens we work with continues to steer our game and curriculum development work, resulting in memorable and meaningful learning experiences that engage them deeply.

For educators and administrators looking to prioritize their students' mental health, social and emotional learning opportunities and the core skill-building they foster can be a powerful and transformative lever.

HERE ARE THREE WAYS TO ENHANCE YOUR SCHOOL OR DISTRICT COMMUNITY'S COMMITMENT TO SOCIAL AND EMOTIONAL SKILL DEVELOPMENT IN TEENS:

1. CALL SOCIAL AND EMOTIONAL SKILLS WHAT THEY ARE: ESSENTIAL SKILLS.

We've written about it before, and it bears repeating. How we talk about something impacts how it is received and regarded. In a world where polarization and hatred threaten our unity, we can't afford to downgrade competencies like self-awareness, self-regulation, showing empathy and care, effectively advocating for ourselves and others, and making responsible decisions for the greater good to "soft skills." Raising the profile of these core skills to an educational and humanistic priority sets the scene for innovative programming and instruction that responds to and addresses students' needs. To quote a member of our Educator Advisory Council, "Education is not an academic pursuit, it's a relational one. They listen to me because of the relationship, not because I'm the teacher." Meeting social and emotional needs is, simply put, the foundation for effective learning.

2. FIND TOOLS THAT EMBED SOCIAL AND EMOTIONAL LEARNING INTO CORE ACADEMIC CONTENT.

Social and emotional learning efforts are powerful when evidence-based tools are embedded into the content students are already learning, and there's often a natural alignment. Our iThrive Sim role-playing simulation games designed for high school social studies classes, for example, build on the natural synergy between civics education and social and emotional competencies. As students collaborate to make decisions that drive each iThrive Sim scenario forward, they expand their civic knowledge while practicing core social and emotional skills like managing stress, regulating emotions, and making responsible decisions. Likewise, iThrive Curriculum's learning units pair with immersive games to support high school English and humanities educators in discussing self- and social awareness, self-management, and relationship skills with their students. As students work through these curricular units together, the narrative at the center of the game becomes an organic springboard for meaningful reflection and conversations about identity, relationships, and communication.

3. ADOPT AN EQUITY LENS.

Emotions and social connections drive learning. In that sense, social and emotional learning is ultimately about ensuring students' preparedness and ability to learn; all students deserve that fair chance. Implementing high-quality and evidence-based social and emotional learning experiences is a key step toward equity in your school or district community. Taking it a step further, social and emotional learning experiences themselves should be designed with equity and access in mind. iThrive's tools are designed to be representative of and accessible to diverse learners in line with our commitment to equity and universal design for learning principles. Gabbrielle Rappolt-Schlichtmann, an internationally recognized expert in learning science and accessible learning, calls our offerings, "the most innovative, integrated social and emotional learning work I've seen in the high school space."

Social and emotional learning opportunities tend to teens' whole selves. They help young people look inward and deepen their ability to know themselves, name their needs, regulate their feelings and behaviors, and embrace others with empathy and curiosity. Committing to these three practices to support social and emotional learning efforts will meaningfully move school communities toward helping students develop core skills and competencies that support their mental health and emotional resilience, setting them up for thriving far beyond school walls.

Teen Mental Health: Five Tips for Making the Most of Your Social Media Use

This post is the next in our series, Supporting Teen Mental Health, which shares tools and insights that support youth-serving adults in showing up for teens in this moment of need. Click here to read the first post in the series about mindfully managing difficult emotions.

Social media use gets a bad rap, and there are certainly reasons for caution. As shared in the U.S. Surgeon General Advisory's recent report on teen mental health, in 2020, 81% of 14- to 22-year-olds said they used social media either "daily" or "almost constantly" and in some circumstances social media use has been linked to poor mental health outcomes.

These findings may be alarming to adults who care about young people and want to protect them online, but as one teen shared with us, "To a high schooler, representation on social media is a huge deal...they don't want authority stepping into their fun zone." Even though guidance and support can be helpful, adults often lead with fear and hammer on the dangers of social media without identifying the opportunities. Yes, we all can strive to be intentional in our use of social media. Adults can model that intentionality. Adults also can reframe social media as one important tool young people and adults can use to support things that matter to them.

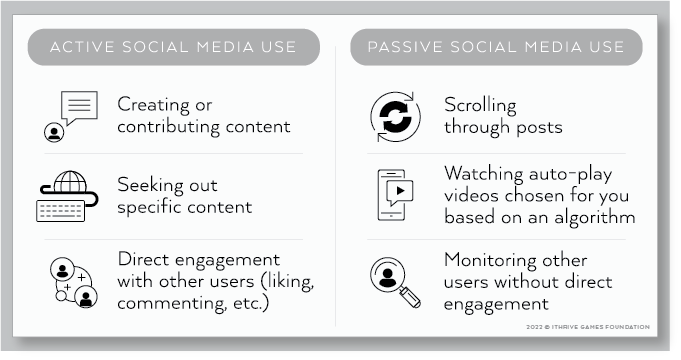

ACTIVE SOCIAL MEDIA USE VS. PASSIVE SOCIAL MEDIA USE

How well social media connects or isolates us depends partly on the behaviors we embody while using it. The Advisory reports on an important distinction between passive and active social media use, highlighting how healthier the latter is.

An active social media user uses its platforms to enrich and simulate real life. They use social media to connect, share and talk to the people they know, and actively engage with communities that offer new perspectives or that share their interests and hobbies. On the other hand, a passive user does not directly engage with others on social media platforms. Instead of actively interacting with others, they wait for content to come to them. Research shows that passive use of social media induces feelings of isolation, sadness, and depression often spurred by viewing the lives of others. If we're all aware of the behaviors that support more positive and healthier experiences on social media, we know which usage patterns to strive for whenever we're online.

HOW TO USE SOCIAL MEDIA ACTIVELY AND MAKE THE MOST OF IT

We spoke to a few of the teens we've worked with to co-create learning experiences for high school classrooms and asked about how they engage with and on social media. Their answers point to how social media, when reframed as a relevant tool for teens and when used actively, supports self-regulation and social connection along with the exploration of self, emotions, thoughts, and interests. Whether you're a teen or an adult, these five tips can help you make the most of social media use so you can post and peruse with purpose:

1. SET YOUR INTENTION.

Why are you going on this social media platform right now? What are you looking for or hoping to feel? If it's simply to escape and avoid anything heavy for a little while, that's valid! Since these platforms are designed to pull you in and keep you on as long as possible, just notice without judgment when your use is drifting from your initial intention and take a pause to bring yourself back to it.

2. CONSIDER SOCIAL MEDIA USE AS ONE PART OF A HEALTHY MENTAL DIET.

Social media use can promote connection and contribute to mental and emotional health when used mindfully and in balance with other healthy behaviors like sleeping enough (7-9 hours for adults, 8-10 for teens), keeping your body moving, spending time with others in person, taking time to reflect on who you are and what you want, and more. Over a few days or weeks, notice what portion of your mental health "plate" social media takes up, and look for opportunities to continue to fine-tune your best balance.

3. CREATE AND EXPRESS.

Especially for teens, social media is a great place to make content and express the many aspects of a dynamic personal identity. Try your hand at making up a dance, sharing artwork, or narrating an experience that reflects who you are and what you care about. You can also make it a point to actively appreciate content you love that others create, like by adding your comments and reactions. This can be a good first step if you typically spend your time online consuming others' content without deeper engagement.

4. FIND YOUR PEOPLE.

Social media platforms connect us to the wider world. What a fantastic opportunity to both expand our perspectives and find others who help us to feel a sense of belonging. For teens, especially those struggling to find acceptance at home or in school for various reasons, reaching out for support on social media can be a lifeline. Search for (or create!) a group around a special interest. Request to join if the group is private, and then introduce yourself to get a conversation and connection started.

5. MAKE A DIFFERENCE.

Now more than ever, social media is a platform that can ignite support for causes that better the world. Teens are so often at the forefront of changes like these. To really level-up your social media use, start an online petition or relief fund and share it with your friends and followers, or look for opportunities others have initiated where you can lend your voice, time, and talents.

Social media offers meaningful opportunities and can be a sacred "fun zone" for teens. If you're an adult who cares about teens, reinforce those meaningful opportunities by highlighting them when you notice them. If you're a teen, consider sharing with the adults in your life about what social media allows you to do for your mental health and what intentional use looks and feels like to you.

At iThrive, we are building engaging learning experiences where teens can experiment without judgment with different ways to express themselves and connect empathically with others. To stay up-to-date on our offerings and the latest posts in the Supporting Teen Mental Health series, sign up for our mailing list today.

Teen Mental Health: Use This 2-Min. Exercise When Difficult Emotions Surface

Unprecedented times come with unprecedented challenges, and the ones that today's young people face are tough to navigate. The data shared in the U.S. Surgeon General's Advisory on Protecting Youth Mental Health confirms this. National surveys show that one in three high school students experiences persistent sadness or hopelessness. The world-shifting consequences of an ongoing pandemic coupled with the big emotions that accompany adolescence make our collective need to support teen mental health and well-being both urgent and necessary.

INTRODUCING THE SUPPORTING TEEN MENTAL HEALTH SERIES

The prevalence of mental health challenges amongst youth requires an all-of-society effort to facilitate the individual and structural changes needed to support and protect teen thriving. Over the next few months, we'll be sharing vetted tools and actionable insights as part of a new five-post blog post series titled, Supporting Teen Mental Health. Mapping back to the U.S. Surgeon General's recommendations, each post will feature helpful tips and resources designed to support all youth-serving adults in showing up for teens in this moment of need.

To kick off the Supporting Teen Mental Health series, here's a quick and effective exercise that can be used and shared with teens (and adults!) to support them in getting grounded when big emotions surface.

PAUSE-BREATHE-NAME: A 2-MINUTE GROUNDING EXERCISE

PAUSE-BREATHE-NAME: A 2-MINUTE GROUNDING EXERCISE

Whether you're a teen or an adult, chances are you've had moments, shifts, and shocks in life that have brought up strong emotions. In those moments, it can be difficult to regulate those feelings. Pause-Breathe-Name is a quick exercise that can help us manage:

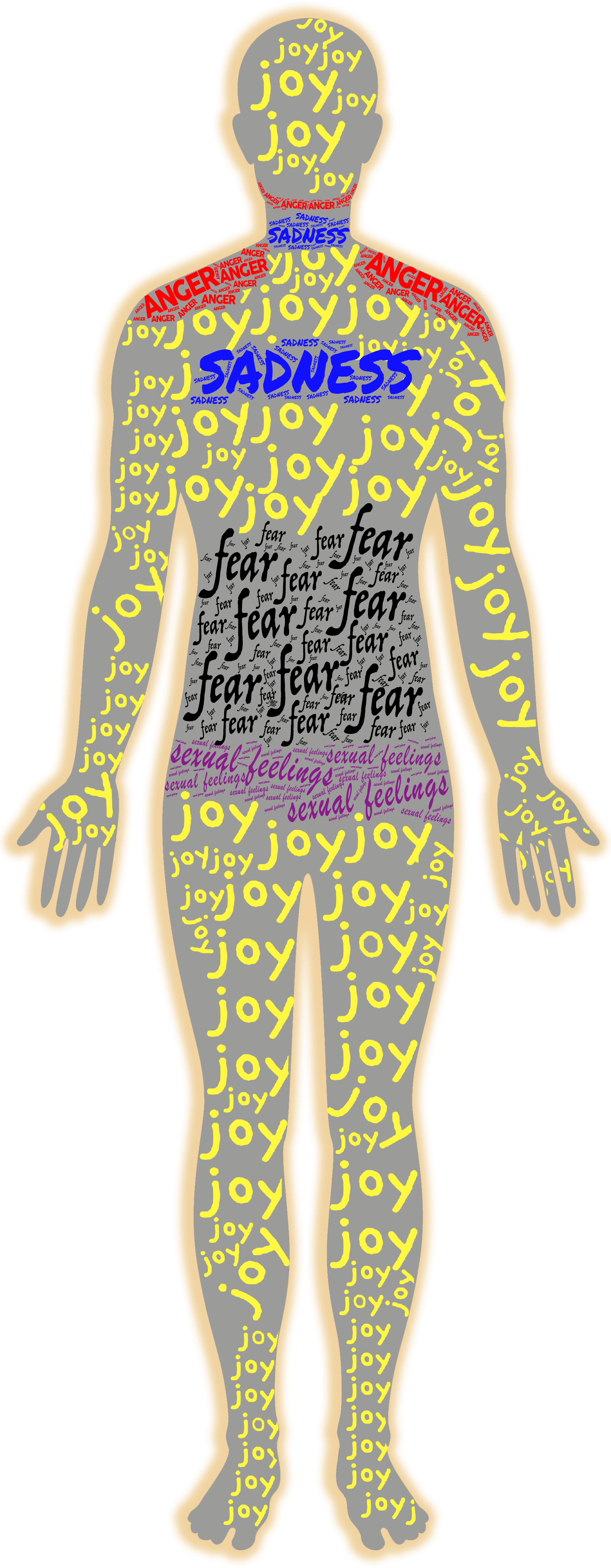

Pause: Start by noticing that a strong feeling has shown up for you and allowing yourself to take a pause before your next word or action.

Breathe: Next, take a couple of breaths. Allow your exhale to be longer than your inhale. This will help to calm your nervous system. As you breathe, try to notice where the strong feeling is showing up in your body. We often feel sadness in our throat, fear in our belly, and anger in our upper back, neck, and jaw. Joy tends to show up all over.

Name: Finally, work on naming the feeling in your head or out loud before returning to what you were doing. The act of naming emotions, especially the more unpleasant ones, actually helps lessen the intensity of those feelings.

This exercise is part of the many social and emotional learning activities in our iThrive Sim role-playing simulation experiences. Students have shared that this exercise has helped them acknowledge moments of discomfort, frustration, and uneasiness they felt while playing as their character, and prepared them to unpack those moments with their classmates. These skills are needed when we have difficult conversations, and practicing these skills helps to strengthen them.

You can use the Pause-Breathe-Name exercise to ground yourself in times of stress and to name the feelings showing up in your body in those moments. What are some other exercises and practices you turn to to get grounded in times of stress? Share with us at contact@ithrivegames.org and stay updated on the latest in the Supporting Teen Mental Health blog series by joining our mailing list today.

Mental Health Awareness Month

Mental Health Awareness Month takes place each year during the month of May. Established in 1949, Mental Health Awareness Month was created to increase awareness around mental health and mental wellness. The National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) reports that 60 million Americans - approximately one in five - experience mental illness in a given year and 50% of all mental illness starts by age 14.

The rate of teens who are experiencing mental health difficulties is rising. We at iThrive Games take these rising numbers very seriously and that is why iThrive offers mental health initiatives that are designed to build social and emotional skills, as well as reduce the barriers to treatment for teens.

Throughout the month of May, we have been highlighting our resources that support strengths-based mental health outcomes through gameplay and more.

Photo from the National Alliance on Mental Illness

What We Do

iThrive's mental health initiatives reveal the power of games for use in therapeutic settings and create supportive experiences for teens to explore identity, wellness, and meaning.

We offer Clinician Guides which are resources for mental health providers who use or want to use games therapeutically. iThrive understands that it is impossible to be knowledgeable about every game a teen client is playing but we also believe that savvy clinicians understand the importance of using clients' passion to pursue treatment goals.

That is why we created these one-page information sheets about popular commercial games that can inform therapeutic discussion and, more importantly, demonstrate genuine interest and support for teen clients.

Our Clinician Guides were created by Kelli Dunlap, PsyD, in partnership with mental health professionals who are familiar with the games and have used them in therapeutic settings. Each guide is reviewed by a licensed mental health professional.

iThrive's resources for educators and parents alike showcase how to use games to engage the whole teen. From curricular resources to an article series and our curated games catalog, our website houses a wealth of information that highlights compelling games that feature mechanics, narratives, and other elements identified by players, professional game developers, game scholars, educators, and scientists that are supportive of habits for thriving such as empathy, curiosity, growth mindset, and kindness. We also offer a Mental Health Design Kit which serves as an informational resource to thoughtful design around mental illness.

The goal of iThrive is to be an ally to teens, including those who are struggling with mental health conditions. We work to create a space and support system to prepare them with the social and emotional skills they need in order to cope with challenging and unfair environments.

Why This is Important

Everyone should have the opportunity to thrive and live their best life. Stigmas surrounding mental health conditions have no room for existence because help is available and there is nothing wrong with seeking it.

HealthyChildren.org says that "9 in 10 teens who take their own lives met criteria for a diagnosis of psychiatric or mental health condition or disorder—more than half of them with a mood disorder such as depression or anxiety." You can find additional information on the prevalence and impact of mental health conditions here.

Change is Needed

Communication is key to making any real change. All people need to feel safe and accepted so that they can open up and let their voice be heard. We want to create space for teens to have the voice, choice, and agency they need for mental wellness. By doing so, not only will they be better able to cope with the many stresses life can bring, but they will also be able to create positive impacts on their communities.

If you'd like to stay up to date with the ways iThrive is working in your community, signup for our newsletter here.

You can also follow us on Facebook and Twitter as we continue to strive to bring awareness to the importance of mental health.

Introduction to iThrive’s Clinicians Guides

Games are a 21st-century cultural competency. Over half the U.S. population and up to 97% of U.S. teens play video games on a regular basis. Games play an important role in how teens socialize. Games foster connections between friends, offering a space for hanging out together, having fun, devising a strategy, and bonding over shared interests.

For professionals who provide mental health services, the likelihood of seeing clients for whom games matter is substantial. Because of the volume of games released each year and the speed at which players move from one game to another, awareness and understanding of contemporary and relevant games is challenging in general. This is especially true for professionals who provide therapeutic services to teens.

The iThrive Games Clinicians Guides are an educational resource for mental health professionals who understand that embracing a teen's passion for games is an opportunity to enhance the therapeutic process.

"I have found iThrive's Clinicians Guides to be useful in therapeutic practice for helping clinicians understand more about virtual worlds, the powerful and positive impact they have on us, and how to provide appropriate and culturally advantageous endeavors with their clients." - Anthony Bean, Ph.D., psychologist and author of Working with Games and Gamers in Therapy: A Clinician's Guide

Created by mental health professionals for mental health professionals, these one-page "cheat sheets" identify key components of specific video games including their themes, characters, and play styles that can be integrated into therapeutic settings. The goal of the guides is to give mental health providers basic information about a specific, popular video game and different ways to leverage a client's passion for the game in the interest of therapeutic or treatment goals.

We worked with mental health professionals to create and review each of the Clinicians Guides. They have all been field tested and refined to be helpful and practical even for those unfamiliar with the games. The games selected represent some of the most popular games available today.

"Not all games are created equal! Understanding the distinguishing features of different video games is key to understanding what role it might be playing in someone's life. iThrive's Clinicians Guides provide the keys to unlock those answers." - Rachel Kowert, Ph.D., psychologist and author of A Parent's Guide to Video Games

The guides are fundamentally grounded in Human-Centered ideology, the belief that a person grows and thrives when they feel valued, validated, connected to others, and understood. In today's media landscape, competency around games is key to providing this experience.

Each guide was designed to provide a foundation for therapeutically-minded conversations with teens about games. All guides contain a brief summary of the game, highlight events or themes in the game that align with therapeutic framing, a list of questions to spark discussion and reflect genuine interest in the person and their game of choice, and a case example of how the game or game content was used in an actual therapeutic setting. Although not every provider has the resources — time, financial, tech-savviness — to have games and game consoles in their office, there is immense clinical and therapeutic value in being able to just talk with someone about the games that are meaningful to them.

"While video games are ubiquitous, not everyone is a gamer. These guides provide succinct, useful summaries for teachers, clinicians, and caregivers to better understand the completeness of what goes on in various games. And, of course, better understanding helps with better communication with those we care about!" - Raffael Boccamazzo, PsyD, psychologist and Clinical Director of Take This

What do you think? We invite you to:

- Use our Clinicians Guides.

- Let us how they worked for you and/or if they can be improved.

- Share with us your game recommendations for our next set of guides.

Collaborate with us! Email us to find out how.

Extra Credits and Mental Health Month

Video games frequently portray characters as having a mental illness but there's little research around those portrayals. This month, we are honored to report that Kelli Dunlap, PsyD, our director of mental health research and design, partnered with Extra Credits to deliver a quick and succinct summary of some of the problems with mental illness depictions in games. Much like Kelli's formal analysis of this topic, Representation of Mental Illness in Video Games, this episode of Extra Credits hopes to offer guidance for future game researchers and developers on how to think critically about the representation of mental illness in games.

Extra Credits is an informative, educational video series about various topics within the intersection of gaming, history, and education. According to Time Magazine,

"Over the course of ten years and hundreds of episodes, Extra Credits has explored a dizzying array of topics, from unraveling gaming's technical mysteries and exploring cultural flashpoints to making history and mythology as much fun to watch as fiction."

While Extra Credits generally covers game-centric topics, they also delve into history, education, and other subject matter. Some of the topics covered by Extra Credits in the past are:

Making Your First Game: Basics - How To Start Your Game Development

The Three Pillars of Game Writing - Plot, Character, Lore

Technical Debt - Improving the Production Pipeline

Extra Credits has turned into a viral YouTube presence with over 2 million subscribers and offering many different channels, including Extra Sci Fi, Extra History, Extra Mythology, Extra Politics, and more. Because of the great wealth of insight Extra Credits has provided to the game development community, we thought a partnership around mental health makes sense.

The episode Kelli co-authored for Extra Credits speaks specifically to the way in which mental illness is portrayed in games. Often times villains or negatively-identified characters are explicitly said to be "insane," "psycho," or "crazy." Using words like this in regards to persons with mental illness, real or fictional, perpetuates and normalizes harmful stereotypes and this kind of irresponsible representation should be addressed by more game developers. The episode lays out a summary of why this topic is important, what can be done about it, and how game developers can move forward to create more responsible depictions of mental illness in their work.

This episode was written as a part of iThrive's initiative to promote Mental Health Month. Some more projects we're highlighting this month are:

Beyond Gameplay

Beyond Gameplay is a podcast where humanity as the core mechanic is the centerpiece. Each episode is a quest to answer a core curiosity — what lives on when the game is turned off? The podcast features Kelli Dunlap, PsyD, interviewing game developers, mental health professionals, educators, and scientists about a wide array of topics. The first episode of Beyond Gameplay, Empathy in Games, will be launching later this month.

Mental Health Design Kit

Twenty-five percent of video games display mentally ill characters. However, there are no guidelines or best practices around portraying mental illness in games. iThrive's Mental Health Design Kit serves as an informational resource to thoughtful design around mental illness. Later this month we release this guide to help game developers take stronger considerations into their depictions of mental health.

Clinician Guides

Another part of our Mental Health Month initiative is our clinician guides. These serve as an educational resource for mental health professionals who use or want to use games as a vehicle for engaging teens therapeutically and on their terms.

Video Games and Suicide Prevention Blog

In this blog, Michelle Colder Carras, Ph.D., discusses how gameplay provides many ways to foster mental health and what role the gaming community can play in suicide prevention. It provides an important and necessary point of view for a growing public health problem.

Sign up for our newsletter to receive early access to these resources and more!

Video Games and Suicide Prevention

If you are experiencing a crisis or having thoughts of suicide, please contact the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255), the Crisis Text Line by texting HOME to 741741, or visit the nearest emergency room.

Suicide is a growing public health problem and the second leading cause of death among young people in the US and worldwide (Hedegaard & Curtin, 2018; World Health Organization, 2018). People may attempt suicide when they feel overwhelmed by problems, pain, and hopelessness but feel they lack the resources or support to cope (Verrocchio et al., 2016). Connecting people to others who can provide mental health support and assistance with coping skills helps prevent suicide (Stone et al., 2017), and video games can play an important role by fostering connections and support. Whether through in-game interactions, membership on teams or guilds of players, or interactions on communication/media platforms such as Discord and Twitch, games offer many opportunities for players to communicate and connect (Colder Carras, Rooij, et al., 2018; Kowert & Quandt, 2016). Recently, video game communities have been tackling the need for mental health support and suicide prevention for their members through a variety of innovative programs. iThrive Games is happy to be talking about our efforts in an upcoming panel called Suicide Prevention in Video Game Communities to be held April 27 at the American Association of Suicidology annual conference in Denver, Colorado.

Famous screenshot from Legend of Zelda (Nintendo, 1986), often used as a meme to encourage others to seek and utilize help.

Many different factors have been linked to suicide. According to one theory, individuals who die by suicide are driven by three factors: feeling that they are a burden to others, feeling frustrated in their efforts to make meaningful connections, and becoming numb to the pain and fear associated with the idea of dying (T. Joiner, 2005; T. E. Joiner et al., 2009). These, along with hopelessness and difficulty with solving problems, making decisions, or seeking help can drive suicide ideation and attempts (Gvion & Levi-Belz, 2018; Joiner et al., 2009). Addressing social isolation/loneliness and problems coping with life stresses can be important targets for suicide prevention programs (Stone et al., 2017). Although about half who die by suicide do not have a mental health diagnosis ("More than a mental health problem," 2018), those who have a diagnosis are more likely to feel like they don't belong (Ma, Batterham, Calear, & Han, 2019). Suicide is a particular risk for some groups such as adolescents, older adults, military veterans, the unemployed, or those with low socioeconomic status (Bryan, Jennings, Jobes, & Bradley, 2012; Nock et al., 2008; World Health Organization, 2018). Members of marginalized groups such as LGBTQI individuals, refugees and immigrants, and indigenous peoples also have higher suicide rates (Forte et al., 2018; Harlow, Bohanna, & Clough, 2014; Hottes, Bogaert, Rhodes, Brennan, & Gesink, 2016).

Preventing suicide is a challenge. Even though we know factors that are associated with more or fewer suicidal thoughts and behaviors, existing prevention programs have yet to make reduced rates of suicide worldwide. One of the most common measures in prevention is gatekeeper training-teaching individuals who are not mental health specialists how to recognize the signs of suicide risk, ask questions about suicidal thoughts and plans and manage suicidal behavior (Stone et al., 2017). Crisis intervention services such as the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline and local call or text centers provide anonymous assessment and counseling by trained individuals who often volunteer from the local community.

Twitter response to the prompt "Tell me about the happiest experience you've had either in a game or because of games? What do they add to your life?"

New approaches to suicide prevention are needed, and recent research has focused on the potential role of video games in suicide prevention. We know that video games help people connect and feel that they belong to a community (Kowert, 2016). Joining teams or guilds, or even just hanging out with people in-game helps players bond through shared activities (Steinkuehler & Williams, 2006; Williams et al., 2006). In a recent study of veterans in treatment for mental health conditions, playing games with others was found to be an important source of social interaction that helped some veterans overcome isolation or assume leadership roles (Colder Carras, Kalbarczyk, et al., 2018). Although taking a break from daily life through games or other entertainment media is a common method of recreation that can help people recharge (Oliver et al., 2015), this study found that some veterans used games to help ward off suicidal thoughts or substance cravings when other coping strategies didn't work (Colder Carras, Kalbarczyk, et al., 2018). Of course, excessive use of games can lead to other problems, so therapists should work with clients to understand the role and uses of gameplay in dealing with life challenges.

Video game groups, researchers, clinicians, and nonprofits are now seeking ways to leverage these potential benefits of video games. iThrive and academic groups such as the Games for Emotional and Mental Health Lab at Radboud University work to develop and promote games that enhance social and emotional learning, reduce anxiety, and teach problem-solving through gameplay experiences. The organization Stack Up provides a host of grassroots, game-related programs that support positive well-being through games, but is best known for its unique online suicide prevention program. STOP (the Stack Up Overwatch Program), which provides anonymous online crisis intervention services and referrals 24/7 for adult members of its Discord server.

Twitter response to the prompt "Tell me about the happiest experience you've had either in a game or because of games? What do they add to your life?"

Other organizations focus on education and messaging to reduce stigma—getting the word out about mental health problems and fostering healthy discussions about coping. The weekly Twitch broadcast PsiStream, led by a licensed mental health counselor, educates viewers about mental health problems and encourages them to ask questions about uncomfortable or challenging topics. The nonprofit organization Take This supports mental health in the game industry through initiatives such as the Ambassador program, which recognizes Twitch streamers who promote positive mental health through their streams. These emerging efforts provide exciting new opportunities to make a difference in suicide prevention and mental health support in the games industry.

Gameplay provides many ways to foster mental health, and the game community is leading the way with innovative programs. Join iThrive on April 27 as we discuss our efforts along with Stack Up and Take This at the American Association of Suicidology meeting. Stay tuned for a link to our live stream on Twitch. And remember that help is available-if you or anyone you know is affected by suicidal thoughts or behavior, contact the National Suicide Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255) or the Crisis Text Line by texting HOME to 741741.

References

Bryan, C. J., Jennings, K. W., Jobes, D. A., & Bradley, J. C. (2012). Understanding and preventing military suicide. Archives of Suicide Research, 16(2), 95-110.

Colder Carras, M., Kalbarczyk, A., Wells, K., Banks, J., Kowert, R., Gillespie, C., & Latkin, C. (2018). Connection, meaning, and distraction: A qualitative study of video game play and mental health recovery in veterans treated for mental and/or behavioral health problems. Social Science & Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.08.044

Forte, A., Trobia, F., Gualtieri, F., Lamis, D. A., Cardamone, G., Giallonardo, V., ... Pompili, M. (2018). Suicide Risk among Immigrants and Ethnic Minorities: A Literature Overview. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(7). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15071438

Gvion, Y., & Levi-Belz, Y. (2018). Serious Suicide Attempts: Systematic Review of Psychological Risk Factors. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00056

Harlow, A. F., Bohanna, I., & Clough, A. (2014). A systematic review of evaluated suicide prevention programs targeting indigenous youth. Crisis, 35(5), 310-321. https://doi.org/10.1027/0227-5910/a000265

Hottes, T. S., Bogaert, L., Rhodes, A. E., Brennan, D. J., & Gesink, D. (2016). Lifetime Prevalence of Suicide Attempts Among Sexual Minority Adults by Study Sampling Strategies: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. American Journal of Public Health, 106(5), e1-12. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2016.303088

Joiner, T. E., Van Orden, K. A., Witte, T. K., Selby, E. A., Ribeiro, J. D., Lewis, R., & Rudd, M. D. (2009). Main Predictions of the Interpersonal-Psychological Theory of Suicidal Behavior: Empirical Tests in Two Samples of Young Adults. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 118(3), 634-646. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016500

Kowert, R. (2016). Social outcomes: Online game play, social currency, and social ability. In R. (Ed) Kowert & T. (Ed) Quandt (Eds.), The video game debate: Unravelling the physical, social, and psychological effects of digital games. (pp. 94-115). New York, NY, US: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group. (2015-20483-006).

Ma, J. S., Batterham, P. J., Calear, A. L., & Han, J. (2019). Suicide Risk across Latent Class Subgroups: A Test of the Generalizability of the Interpersonal Psychological Theory of Suicide. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior, 49(1), 137-154. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12426

More than a mental health problem. (2018, November 27). Retrieved April 15, 2019, from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website: https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/suicide/index.html

Niederkrotenthaler, T., Voracek, M., Herberth, A., Till, B., Strauss, M., Etzersdorfer, E., ... Sonneck, G. (2010). Role of media reports in completed and prevented suicide: Werther v. Papageno effects. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science, 197(3), 234-243. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.109.074633

Nock, M. K., Borges, G., Bromet, E. J., Alonso, J., Angermeyer, M., Beautrais, A., ... Williams, D. (2008). Cross-national prevalence and risk factors for suicidal ideation, plans and attempts. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science, 192(2), 98-105. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.107.040113

Oliver, M. B., Bowman, N. D., Woolley, J. K., Rogers, R., Sherrick, B. I., & Chung, M.-Y. (2015). Video Games as Meaningful Entertainment Experiences. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 5(4), 390-405. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/ppm0000066

Steinkuehler, C. A., & Williams, D. (2006). Where Everybody Knows Your (Screen) Name: Online Games as "Third Places." Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 11(4), 885-909. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2006.00300.x

Stone, D., Holland, K., Bartholow, B., Crosby, A., Davis, S., & Wilkins, N. (2017). Preventing Suicide: A Technical Package of Policies, Programs, and Practices. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Williams, D., Ducheneaut, N., Xiong, L., Zhang, Y., Yee, N., & Nickell, E. (2006). From Tree House to Barracks: The Social Life of Guilds in World of Warcraft. Games and Culture: A Journal of Interactive Media, 1(4), 338-361. https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412006292616

World Health Organization. (2014). Preventing suicide: a global imperative. Retrieved from https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/131056/9789241564878_eng.pdf?sequence=8

World Health Organization. (2018). National suicide prevention strategies: progress, examples and indicators. Retrieved from https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/279765/9789241515016-eng.pdf?ua=1

Exploring the Intersection of Video Games and Mental Health

MAGFest 2019 - A Compilation of Panels, Playtesting, and so much more!

Kelli Dunlap, PsyD, director of Mental Health Research and Design at iThrive Games, playing our Critical Strengths Engine (CSE) as she helps a new playtester facilitate the game for the rest of the group.

With over 20,000 people in attendance, iThrive Games was beyond excited and thankful for the opportunity to be a part of MAGFest for the third year in a row. This annual event celebrates music and games while attracting attendees, speakers, musicians, and cosplayers from all over the world. MAGFest enables us to be surrounded by like-minded individuals who believe in promoting prosocial outcomes.

Showcasing iThrive's Critical Strengths Engine

MAGFest Indie Tabletop Showcase featured iThrive's Critical Strengths Engine (CSE), a pen and paper role-playing game ruleset for exploring and supporting social and emotional skill development.

In 2017, Ian McDonald posed this question to us at one of our game jams,

"What if there were a system for tabletop role-playing games (TTRPGs) based around social and emotional attributes like emotional integrity, instead of strength and dexterity?"

To say this piqued our curiosity is an understatement. It launched the idea for the CSE and we've been working on it ever since!

We designed the CSE to be accessible and enjoyable for all players, and were especially mindful in our development that it meet the needs of mental health professionals working with teens.

At the MAGFest panel, The Making of a Therapeutic RPG, iThrive's Kelli Dunlap, PsyD, director of mental health research and design, and Sean Weiland, producer, talked about the collaborative design process for the CSE and shared lessons learned in development and during playtesting. Also on the panel were our CSE collaborators, mental health provider and executive director of the Bodhana Group, Jack Berkenstock, and game designer, Max Raabe. We shared with the audience the unique rewards and challenges of designing with a truly interdisciplinary group, and how we strove to balance fun, a strengths-based focus, engaging stories, and therapeutic relevance.

Jack Berkenstock, mental health provider and executive director of the Bodhana Group, playtesting with a group of eager participants.

During development, our design team at iThrive went through 10 versions of the CSE character sheet. This game structurally lets players bring characters to life by engaging with their strengths and deficits via the "Whys" or circle of character motivation. Therapy often necessitates interacting with difficult issues. We consciously observed and allowed for the CSE to be an analogue where players can use characters to engage with issues that are difficult for them.

Following the panel discussion, 20 people joined us to playtest the CSE. Not only did this playtest extend past midnight, but it was also the largest concurrent playtest of the CSE to date! Playtesters thoroughly enjoyed taking part in the CSE playtest and it was delightful to watch both teams work together within the system of the CSE to solve problems and overcome obstacles that were thrown in their way. Some of the feedback we received from participants included the following,

"Positive! Refreshing! Great to think of solving solutions with emotional strengths rather than physical ones."

"I had a lot of fun! It was neat to focus on motivation."

"Very positive, lots of fun. Far more [than] we would have in another system with no combat. I liked how this focuses on other aspects of traveling/adventuring."

The CSE officially launches this Fall and includes four unique adventures: an official Pugmire story by Eddy Webb; Alteris, a contemporary science fantasy story by Toiya Finley; Dust, a post-apocalyptic survival game by James Portnow; and a fourth untitled story by Bodhanna Group founder, Jack Berkenstock.

Max Raabe, game designer, leading a playtest just after the panel on creating a therapeutic RPG.

Toward A New Vision of Mental Health Representation in Games

Kelli Dunlap spoke on a panel with Tanya DePass, and its organizer Meg Eden on the Mental Health Representation in Games. With standing room only attendance, this panel discussed important issues surrounding the representation, diversity, and accessibility of mental health in games. In addition to sharing their favorite examples of the representation of mental health in games, and tropes and ideas to be avoided, panelists expressed their hopes for what mental health representation could look like in future games.

Tanya said,

"I'd like to see people and characters have mental health as just a matter of course for their character and not have it be the be-all end-all. If a character needs meds or something like that just like everyday life for those that take medication it's not big deal, it's not like 'oh woe is me I have to take meds everyday to regulate my brain, therefore, I'm a garbage human' that a lot of us fall into.... This is something that is part of me and move on with it."

Kelli responded with,

"I would love for there to never be another horror game that uses an asylum ever... We see asylums or mental health institutions or psychiatric hospitals as a shorthand we use in media for 'Be afraid. Be very afraid. Bad things are going to happen.' Has anybody ever played a video game where you woke up in an insane asylum and something good happened to you immediately after? No. The trope is dead. Kill it."

The panelists also answered questions about respectful and ethical ways of dealing with difficult mental health topics within the game design process,

"Give players the chance to opt out of something. You don't know anyone's experience when you're programming a game or what's happening... Things like warnings or give me the chance to opt out or fade to black or something like that because I was not ready to deal with that scene at all." - Tanya DePass

"Games are such a creative medium that you can [do that] in creative ways that can actually benefit the design of the game. Allowing for those options can actually branch into a unique gameplay experience. It doesn't have to limit you." - Meg Eden

After the panel, one of the attendees shared his appreciation and excitement with Kelli saying, "I didn't think a game about ADHD is possible, but after your panel, I think it is and I'm excited to get started."

Keep The Conversation Flowing

At MAGFest, the fun never ceases and the conversations are always flowing. We are so grateful for the opportunity to meet with more people who aim to work to benefit teens at the intersection of game development, education, and mental health. We especially appreciated being part of the Music and Games Education Symposium (MAGES), of MAGFest, where we presented on topics related to the personal and social impact of mental health representation in games, strategies around self-care and confronting impostor syndrome, and designing for cooperation. If these topics interest you and you want to keep up-to-date with all of the happenings and projects here at iThrive, please sign up for our newsletter.

Game designer Max Raabe and Sean Weiland producer at iThrive Games (top left), the tabletop role-playing game (TTRPG) panel (top center), Kelli Dunlap, PsyD, director of Mental Health Research and Design at iThrive (top right), Jack Berkenstock executive director of the Bodhana Group, Max Raabe game designer, Sean, and Kelli (Bottom)

Grief and Job Loss: Tips for Coping with the Social and Emotional Impact of Layoffs

Kelli Dunlap is the director of mental health research and design at iThrive Games. She holds a doctorate in clinical psychology and directs iThrive's mental health and game development initiatives.

On Tuesday, February 12, games publisher Activision stated it would be laying off 8% of its workforce - about 800 people - despite record profits in 2018. Mass layoffs in the games industry are not uncommon, nor are exploitative working conditions (i.e., crunch) and job insecurity. In response to recent events similar to the Activision layoffs, there's been a call to unionize the games industry and confront current common practices in the games industry such as crunch and "feeding game developers to the machine." Addressing the current work culture is critical to the future health of the industry and its workforce, but large systemic changes take time. So what's a person to do in the meantime?

Activision Blizzard cuts hundreds of jobs despite "record-setting" revenues: https://t.co/J07hoNhWj5 pic.twitter.com/jexBaNiQ1E

— Polygon (@Polygon) February 12, 2019

After the layoffs were announced, there was ー and continues to be ー an outpouring of support over social media offering condolences, commiseration, and job openings. Some of those directly impacted by the layoff took to social media to share their grief:

Today was my last day at Blizzard Entertainment. I knew that layoffs are commonplace in the video game industry, but I somehow always thought that if I could work really hard, get the right education, and be an exceptional employee that they'd never happen to me. I was wrong.

— Jennifer Mallett (@Jen_Mallett) February 13, 2019

Job Loss and Mental Health

Grief is the body's reaction to loss. Any loss that disrupts a person's sense of self-worth or the stability of their livelihood can be grieved. Job loss is no exception. Decades of research has shown that loss of employment, especially when it is unexpected, can have a psychological impact similar to when a loved one dies.

Losing a job can set off a cascade of additional losses, some obvious like loss of income, health insurance, and financial security, and some less obvious like loss of social status,

For every time in my life that I've had a pit in my stomach, I still cannot begin to imagine the grief of those affected by the Activision Blizzard layoffs today. It's truly terrifying, and I wish them the absolute best in this trying time.

— Brian Turner (@BT_HawkGuy) February 13, 2019

For Those in Grief

For those grieving the loss of their jobs, their security, their livelihood, it's critical to remember that grief is not about passing through set stages from denial to acceptance - everyone's path through grief is unique and often complicated. It is absolutely okay to not feel okay, to feel your feelings, and to not instantly spring back as though nothing happened. Searching for a job can be just as distress-inducing as losing a job, so take the time to take care of yourself. Small things like listening to your favorite song, eating a comforting meal, connecting with friends, snuggling a pet, can buoy you while you're riding waves of emotions.

Grief extends beyond emotions and can impact physical, social, and cognitive abilities. People in grief may experience physical symptoms such as difficulty sleeping, fatigue, digestive problems, social symptoms like feeling isolated or withdrawing from others, and cognitive symptoms like difficulty concentrating and self-blame.

If you're feeling overwhelmed, reach out to someone you feel close to that will listen and not jump to "fixing" the situation. Setting up boundaries for the conversation can help you get your needs met and make the best use of your support. For example, "Hey, I'm having a tough time. Can we talk?" invites a back-and-forth conversation whereas "Hey, I'm having a tough time and need to vent. Not looking for answers, just a supportive ear" clearly conveys a desire to be heard and validated without judgment or troubleshooting.